If you’re a golf course superintendent, it’s not unreasonable to assume that you, or perhaps members of your crew, are currently playing around with a drone on the property. They are amazing tools, these drones, and great fun. But most golf course personnel (superintendents included) tend to treat their drones as something of a novelty or diversion. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that, but the frivolity of that usage doesn’t limit the legal requirements or liabilities involved.

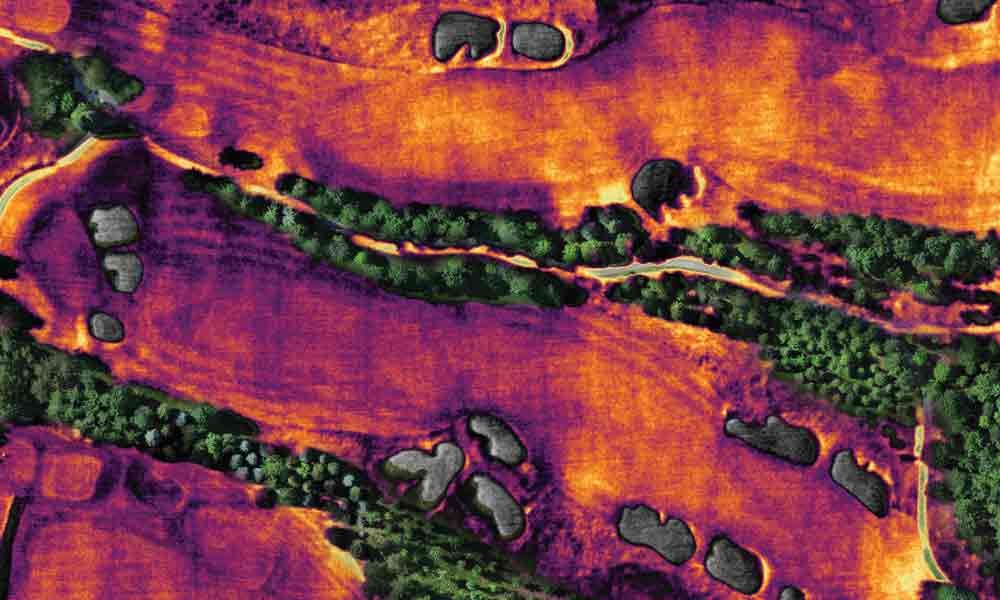

Because my company provides golf course superintendents with drone-enabled multi-spectral and thermal imagery, we’re intimately acquainted with the relevant laws and insurance procedures. I’d love to tell you how our data helps clients save money on water usage, establish chemical-application efficiencies, and ward off potential turf disease. But that’s not what this column is about.

Our client clubs need not worry about the legal and liability issues surrounding drone usage because those responsibilities fall to us, the vendor. Even so, all superintendents should better understand their own obligations in these areas. What our company does, professionally, and what you’re doing recreationally might be apples and oranges, but the same rules and risks apply to everyone.

Legality

Many folks are under the impression that if they aren’t selling drone services to someone — if they’re just messing around with a drone on a privately owned golf course — the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) doesn’t really care. Well, that’s not the case. If you or someone on your staff is operating a drone on your course, that is not “recreational” usage according to the FAA. It is professional/commercial usage because money is being exchanged at your facility in order for golfers play the course, or for members to belong to the club where this drone operation is taking place. Accordingly, whoever is operating that drone on your course is required to obtain FAA licensing.

There are two ways to achieve this. The first is obtaining a 333 Exemption from the FAA. Essentially, the FAA has created an exemption for an aircraft with no pilot on board. However, to operate under this exemption, a licensed aircraft pilot is required on the ground to operate the drone.

As my Chief Business Development Officer Justin McClellan is fond of saying, ”I haven’t run across too many assistant supers with their pilot’s license.” Most people don’t have one, to be fair. And that’s why the FAA, in September 2016, created Part 107 of the Federal Aviation Regulations, which stipulates that would-be operators of commercial drones must first pass a remote pilot exam, which requires probably 10-16 hours of study and a fee to take the test.

The priority here is safety: Each time that person puts a drone up, the FAA requires the licensed operator to first assess current weather conditions and determine if there are any temporary air-space restrictions in place (just in case the president is speaking at some nearby high school). This remote pilot is also responsible for performing a safe, emergency landing, if necessary. If your course is less than 5 miles from an airport, you are likely within airspace controlled by air-traffic control. Accordingly, you’ll need a Part 107 Airspace Waiver or Airspace Authorization, which clears the licensed operator to fly in that controlled air space.

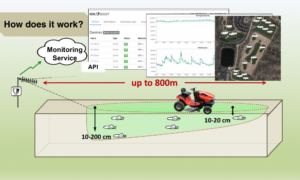

For do-it-yourselfers, there are a few good apps that provide weather and airspace restrictions, and the burden here isn’t gigantic. As a company, we handle all this stuff for our client clubs, and we do so by essentially deputizing the superintendent or someone on his/her staff as the designated remote pilot. We supply him/her with an online study course and pay their test fee. When they pass, they are legal under Part 107 and serve as our on-site remote pilot to verify weather and look for other aircraft.

Of course, the FAA doesn’t have its own police running around, making sure everyone with a drone is flying in compliance, which helps explain why there are so many folks flying their drones casually, without a license. All the same, if some airline or Cessna pilot reports someone on your staff, or God forbid there’s a crash? Well, don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Liability & Insurance

Here’s a good way to think about drone usage and insurance: Your current club/course policy surely covers your maintenance crew and the fact they operate mowers, climb in and out of bunkers, etc. But what about climbing and pruning trees? My guess is you’d be dubious — and quickly call the insurance company to account for that specialized activity.

That’s an anecdotal way of saying that drone operation is almost certainly not covered under your current club policy.

Again, our clients don’t have to worry about this. Our drone activity on and above their properties is entirely accounted for under coverage maintained by my company’s insurance. Let me tell you about that coverage — not to brag, but because it will inform the way you should be thinking about casual-but-commercial drone use at your club.

My company maintains a general, corporate liability policy for our employees who drive cars, visit course sites, drive Gators, do survey-type work, etc. But that policy does not cover the drone-operation aspect of our work. We have a separate policy for each individual drone we own. Every time we put a new one into service, we call the insurance company, supply the serial number, and pay a bit more. Our insurance vendor frankly doesn’t care too much what the FAA rules are; he priced our policy after assessing and evaluating our drone systems, operating practices and experience.

In short, if someone on your maintenance crew is flying a drone at the club, call your insurance company and get this covered. Or ground the drone until such time that you do.

Here’s the good news: Our original drone-specific quote was pricey, but when the adjuster came out and observed/assessed the way we do things, he cut our rate in half. Golf usage is pretty low risk; courses are sparsely populated compared to many places where folks might wish to fly drones. But here’s the sobering news: Our example and the example of you and a member of your crew flying a drone casually are, again, apples and oranges. Our drones are flown by software. We fly the same pre-programmed GPS flight patterns every day. Our battery voltage is monitored continually — if it’s running too low to complete a flight, the drone automatically returns home. In other words, there is very little chance of pilot error, or hitting a tree, or crash landing and putting anyone at risk.

I don’t want to belittle or condescend to amateur drone enthusiasts; our company is almost entirely drone enthusiasts. This year we are expanding our drone operations to about 50 different courses across North America, and we’re frankly thrilled to find someone on staff, at a new client club, who knows something about drone operation. That person is invariably enthusiastic about what we’re doing and easier/cheaper to train for eventual licensing.

But if that enthusiast isn’t licensed and the club’s insurance doesn’t account for specific risk, I’d politely direct this employee to fly somewhere else recreationally, at his own risk.

James Peverill is chief executive officer at GreenSight (www.greensightag.com), a Boston-based technology firm whose drone-enabled golf course service provides superintendents actionable evapotranspiration, plant health and application-efficiency information on a daily basis.