This column features recollections of the author’s 34 years as a golf writer. These installments stem from his many travels and experiences, which led to a gradual understanding that the game has many intriguing components, especially its people.

At first glance, one might not have seen Dr. Joe Gruss as someone special. But, after scanning his medical bona fides, one would learn that he truly was a remarkable person. To me, Joe was a golf- and fun-loving guy who traveled everywhere with his clubs and played some of the best courses in the world. Yet he was also a highly skilled plastic and craniofacial surgeon who used his technical brilliance to tackle the most challenging of cases, improving hundreds of lives in the process.

Born in Johannesburg, South Africa, Joe attended medical school at Whitwatersrand and practiced there before moving to England and working at hospitals around Europe. According to his colleague and golf buddy, Dr. Ken Jaffe, “He was the chief of the world-renowned trauma unit at Sunnybrook Hospital – the largest trauma center in Canada – and was associated with the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. He was later recruited by the University of Washington School of Medicine and Children’s Hospital in Seattle, where he took care of children with congenital defects, and at Harborview Medical Center, where he worked on adults with severe craniofacial trauma.

“By the time he arrived in Seattle, Joe was already an international figure. It wasn’t until the day I attended the first annual Joseph Gruss Lectureship that I understood how truly famous he was around the world. His office was near mine and we played countless rounds of golf together. But Joe never really talked about what he did, nor all of his innovations in craniofacial surgery. Only when the people at this event talked about Joe being such an innovator did I to get a perspective on all of his significant accomplishments.”

American Society of Plastic Surgery (ASPS) member, Peter Neligan, knew Dr. Gruss for more than 30 years. He was a Fellow in Toronto at the same time Joe was a young attending physician. Both Drs. Neligan and Gruss eventually ended up in Seattle. Neligan maintains that Joe was always “kind and an inspiration to everyone,” as well as incredibly humble for someone who had amassed such impressive achievements.

The medical breakthroughs by Dr. Gruss were manifold, but some were fraught with initial skepticism by others within his specialized community. “Joe was a thought leader and didn’t follow the crowd,” said Dr. Richard Hopper, another colleague. “He always sought new approaches and was also a leader in pediatric surgery. For example, he introduced using little plates and screws to fix broken bones under the skin for facial trauma. He got a lot of flak for that early, but then went around the world and introduced it and that became the standard. He stuck to his guns, weathered the criticism and people soon realized he was right.

“His thoughts were way ahead of the times,” added Dr. Hopper, the Division Chief of Plastic Surgery and Director of the Craniofacial Center at Children’s Hospital. “Another example: Babies’ skulls at the back of the head were being reshaped in the 1980s and Joe determined this issue resulted in many unnecessary surgeries. Joe proved that mothers did as told to lie their babies on their backs, which led to flatness on the back of the head. Joe was the first to realize that this recommended sleeping position, along with the softness of the babies’ heads, was the cause. As a result, Joe helped reduce the number of unnecessary skull-reshaping surgeries on young babies and helped develop effective non-surgical treatments for this condition.

“He came up with a lot of other neat ideas,” added Dr. Hopper. “He not only originated a technique but had the stick-to-it-iveness to prove it and do things right. Surgery is like carpentry, and there are different ways to do something. Joe developed an international reputation. People always listened to Joe because he was so thoughtful and innovative.”

Dr. Gruss introduced immediate bone grafting and internal fixation for complex facial fractures. Though initially met with criticism, it is now “taken as dogma,” noted Dr. Hopper, who enjoyed a strong personal relationship with his co-worker. “Joe was my No. 1 guy to work with. He was my confidant, partner and role model. He always supported his staff and did what was best for the team. He let others in his group grow in their careers and didn’t hold them back, even if it meant he had to step aside. He had a healthy ego, but that never stopped him of thinking of others, both patients and partners.

“If I ever needed somebody to back me up, Joe was always there for me,” added Dr. Hopper. “He didn’t suffer fools gladly, and if Joe said something wasn’t good, you knew you had to look into it and that ‘something’ needed to be fixed.”

Joe took on the toughest challenges, regardless of skin color or economic background. He loved people and embodied his genius. Just one example is Muhammed “Hamoody” Jauda (Google the name to see how everything turned out). The 3-year-old was shot in the face by Sunni insurgents in his native Iraq and, fortuitously, was airlifted to Seattle to be treated by the world’s preeminent expert in treating such dire cases. Dr. Gruss, with assistance from other doctors at Children’s, painstakingly coaxed a human face from the boy’s scar tissue. Hamoody now lives with a couple in Snohomish, Washington, far from the dangers of his home country.

One theory Joe formulated, in 1973 at Sunnybrook Medical Centre at the University of Toronto, was that results could be improved if surgeries were done as quickly as possible, grafting the patient’s own bone into the damaged area before scar tissue formed. This, too, led to reprisals within the medical community. Other doctors not only refused to use his techniques but advised students that when Gruss was teaching not to listen to him. His papers were initially rejected by medical journals. “It was contrary to all the textbooks and I got severely criticized,” he told reporter Nancy Bartley in a December 2008 Seattle Times story. “I was just a young doctor, and it was very hard for me.”

But, by the time he moved to Children’s Hospital in Seattle with his wife, Eve, and daughter, Jennie, Joe was greeted with a seemingly endless supply of young patients with horrific birth defects. Their parents had been told nothing could be done. “There were hundreds and hundreds of kids who had never been operated on. Kids who were 10 to 12 years old,” Dr. Gruss told Bartley. Some had eyes on the side of their head, two noses, a face flat as a lollipop. “They had saved all these patients for me,” he said.

I learned all these remarkable achievements of Joe’s – a fellow member at Sand Point Country Club in Seattle – only after his death, from pancreatic cancer, on June 26, 2019. I regarded him as a friendly and dedicated duffer who knew me as a golf writer. Usually soon after returning from yet another enviable international golf-medical junket, Joe enthusiastically detailed the latest and greatest courses he’d just played, always closing with: “Jeff, you have to go there!”

These weren’t just any old dog tracks; they were top-shelf courses in Europe, the Far East, Australasia and Africa – sites where he helped spread techniques that saved the lives of untold children and adults. Among his stops were top-100 courses Royal Melbourne, Kingston Heath, Royal Birkdale, Ballybunion, North Berwick, Royal Dornoch, Barnbougal Dunes, The National Golf Club (Gunnamatta), the Cape Wickham and Ocean Dunes courses on King Island in Tasmania, Merion, and Pine Valley in New Jersey.

Another fellow doctor/golfer, Bryan Williams said this of his buddy’s peregrinations. “Joe was a highly regarded international speaker covering the full range of his special skills in reconstructing the faces and skulls of children born with incredible deformities and the burdens that go with it. Joe was, at heart, a teacher and, frankly, the international groups that wanted to have him for a lecture learned early that if they could arrange a couple days of golfing at nice courses, he would be happy to travel anywhere in the world. I think that Joe played more different international courses than anyone else. His motto was: ‘Have golf will travel.’ “

From his obit: “Dr. Gruss trained 52 craniofacial Fellows who now practice around the globe. In 1998, he became the first holder of the Marlys C. Larson Chair in Craniofacial Surgery at the University of Washington. His honors include the AAPS Distinguished Fellow Award; the ASMS Lifetime Achievement Award; and an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. In January (2019), the Seattle Children’s Hospital celebrated Joe’s career with the first Gruss Lectureship, where he was joined by colleagues and Fellows.”

“Dr. Gruss asked his family not to have a memorial for him after his death,” Dr. Hopper said in an ASPS obituary. “He said that lectureship in Seattle in January with his friends and Fellows from around the world was his eulogy. All he asked was that his wife, Eve, and daughter, Jennie, scatter his ashes on the last green at St. Andrew’s in Scotland.”

Drs. Jaffe and Williams, also Sand Point members, were close to Joe at work and play. Before retiring, Jaffe’s last position at Children’s Hospital was the Director for the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine. “I was also Professor of Rehabilitation Medicine and Adjunct Professor of Pediatrics and Neurological Surgery at the UW. I now serve as Professor Emeritus and Senior Advisor at Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center. This is one of eight CDC-funded sites in the U.S. and the only one west of the Mississippi River.”

Dr. Williams has a similarly impressive résumé. “I taught at the University of Detroit, had a private practice, was on staff at three hospitals in Windsor, Ontario, as well as Children’s Hospital of Michigan and was the Director of the Windsor-Essex Maxillofacial Speech Team that provided multidisciplinary care for children with cleft-palate and facial deformities for southwestern Ontario. I was recruited by Children’s Hospital and started in January 1991 as Director of the Department of Dental Medicine. My primary clinical activities were with the Craniofacial Team and, in short order, Joe and I were working very closely together in the care of many patients. I continued to maintain professional and personal contact with Joe until his passing.”

Dr. Jaffe: “Because of his amazing international connections, Joe had trainees and colleagues from all over the planet come to work with him. He truly was a citizen of the world. He traveled probably more than any other faculty members I can think of. He was guest lecturer in Japan, Australia, England, South Africa – he logged hundreds of thousands of miles on United Airlines. I made many trips with Joe and, upon seeing him at check-in, they rolled out the red carpet. He was a great guy to travel with. When Joe arrived at an airline lounge, the waiter would say, ‘What would you like with your caviar today, toast points or crackers, Dr. Gruss?’ “

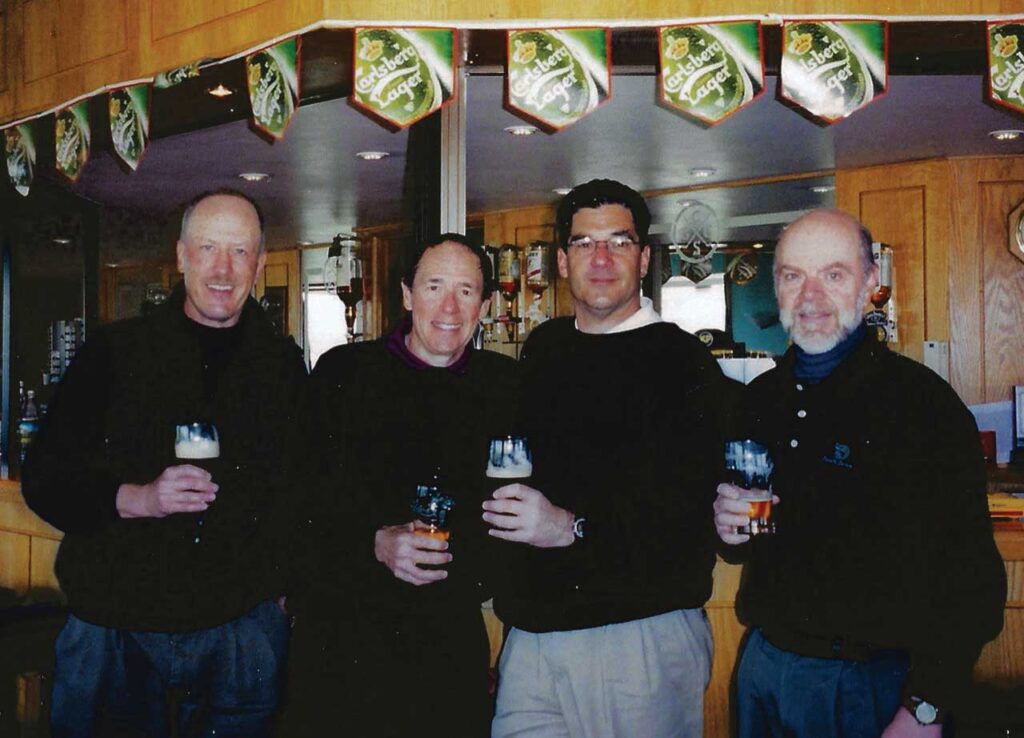

Drs. Gruss, Jaffe and Williams went on regular golf sojourns to Ireland, along with another talented pediatric urology surgeon, Mike Mitchell. “We always went in April so we didn’t have to contend with tourists. But the downside is the weather was often rainy and windy,” said Williams. “Joe was the ideal guy to be the leader on these trips. First, he grew up in South Africa and was a natural driving on the left side of the road. Secondly, early in his career before doing his surgical specialties, he worked as a traveling physician in Ireland and knew the country like the back of his hand.

“Joe was the ultimate ‘mudder.’ I used to say that if I wanted him to play well, I should dump a bucket of water over his head,” added Dr. Williams with a chuckle. “Most of the time there were only local golfers on the course. At lunch we would be ‘chatted up’ by some who wondered why the devil we were out in such lousy weather. We would always say we were from Seattle and played in this most of the year. Once, because of nasty weather, we were the only group at Waterford, Payne Stewart’s favorite course. A single came up behind us around the 12th hole. The guy was wearing a Mariners hat and lived north of Seattle!

“In the evenings we always went to a local pub for dinner and were entertained by Joe’s great golf and non-golf stories. My special privilege for the evening – other than listening to Joe’s tales – was that I usually drove us home because I have a one-beer capacity and Joe, Ken and Mike enjoyed sampling different fine Irish whiskeys.”

The foursome also ventured to the American links Mecca of Bandon Dunes on southern Oregon’s Pacific Ocean coast. “On these trips we were often joined by former residents of Joe. The feelings of these incredibly talented people about Joe were very evident,” Dr. Williams noted. “I believe his legacy should be a fine model for every teacher.”

Dr. Joe Gruss is missed not only by his associates in the medical profession, but by all the golfers who had the honor of accompanying him during a round. I have come across a lot of interesting people over the years. Joe was certainly one of the most memorable I’ve ever met, whether on the golf course or off.

Jeff Shelley has written and published nine books as well as numerous articles for print and online media over his lengthy career. Among his titles are three editions of the book, “Golf Courses of the Pacific Northwest.” The Seattle resident was the editorial director of Cybergolf.com from 2000-15. For seven years he served as the board president of First Green, an educational outreach program that is now part of the Golf Course Superintendents of America and Environmental Institute for Golf.

Read other in Jeff’s Series of Making the Rounds – https://golfcoursetrades.com/author/jshelley/